The Eleusinian Mysteries were open to men and women irrespective of age or social status. In the early period, the participants would have been limited to the members of certain Eleusinian families, whose ancestors had received the content of the Mysteries by goddess Demeter. Gradually, however, the cult opened up, and an initiation process was adopted to allow all those interested in enjoying the benefits and delight offered by participating in the sacred rituals. According to mythological tradition, the first foreigners welcomed into the Mysteries were Heracles and the Dioscuri. After this impressive vote of confidence in the Mysteries’ potential, the Athenians (initially) and then all the Greeks were accepted as candidates for initiation. However, a prerequisite for participation was the understanding of the Greek language. Moreover, prospective initiates should not have shed innocent blood, while the Persians were excluded because they destroyed many Greek temples during the Persian invasion in 480 BCE.

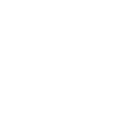

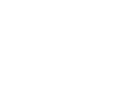

The introduction of Hercules and the Dioscuri, Castor and Pollux, in Eleusinian mysteries, Auguste-Gaspard-Louis Desnoyers, c. 1844-1861, engraving, The New York Public Library © The New York Public Library

The Homeric Hymn to Demeter clarified the benefit of initiation for the faithful. The mortals who received the love of the goddesses were the happiest people. Demeter would send Plutus to them with all the goods that the god was famous for delivering. The initiates (mystai) were even more optimistic because they had a reasonable hope for a better afterlife. Only those initiated in the Mysteries would fare well in Hades’ dark realm, while the ignorant would suffer untold miseries. Trygaeus in Aristophanes' “Peace” goes so far as to borrow money to secure his initiation before he dies. At the same time, Dionysus sees the initiates dancing and joking in green meadows. For those who were initiated, the Underworld is full of light and they form happy choirs in myrtle coppices.

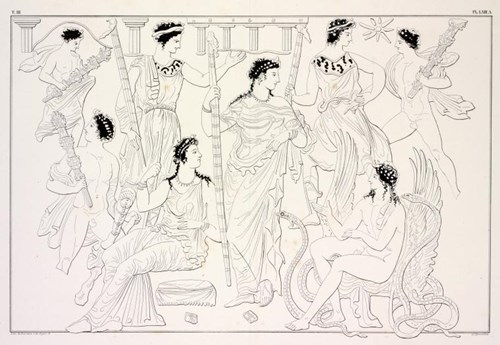

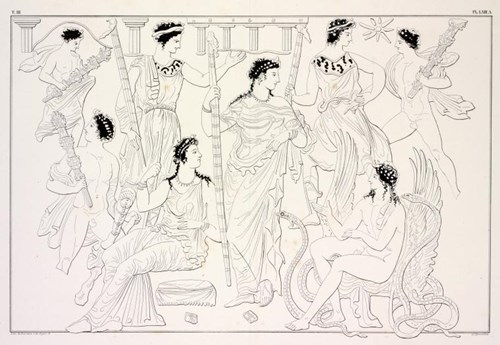

Demeter, Dionysus and Persephone, c. 1844 - 1861, engraving, The New York Public Library © The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library

The initiation process began with the voluntary participation of prospective mystai in the Lesser Mysteries. Members of the sacred Eleusinian families of priests that ran the Mysteries (the Eumolpidae and the Kerykes) served as mystagogoi (mystagogues). The preparation probably consisted of information about the afterlife, the basic principles of the Eleusinian cult, the terminology and landmarks associated with the Mysteries, and the inviolable principle of secrecy that governed the process. The first initiation stage established a bond between the candidates and the teachers. For example, Dion of Syracuse (408-354 BCE) was connected through initiation with two brothers from Athens, Callipus and Philostratus. When the brothers visited Sicily and saw with their own eyes Dion’s tyrannical behaviour, they killed him because his infamous and sacrilegious attitude disgraced the whole city.

Dion’s story serves as a reminder of the importance of the bonds between mystai and mystagogoi (Callipus had served as Dion’s mystagogos). Generally speaking, though, mystai did not form a distinct group to achieve a particular goal. Instead, initiation was a personal choice. Beyond a sense of belonging to a majestic and sacred ritual, the bonds between the faithful were essentially broken at the end of the celebration and their return home.

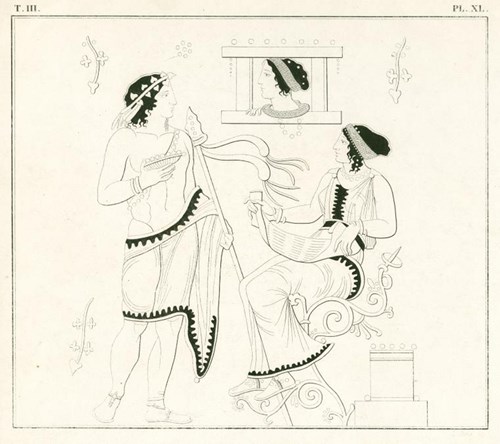

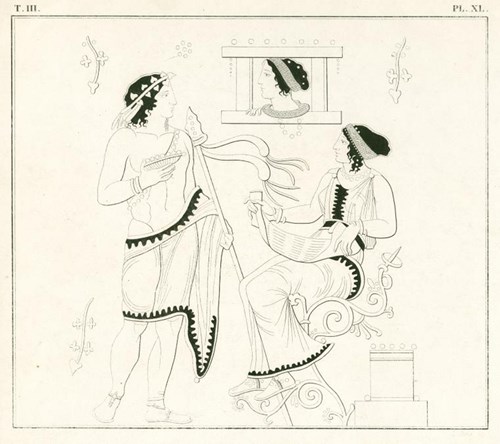

Demeter, Persephone and initiants, 350-300 BCE, sculpture, Musée du Louvre © 2006 Musée du Louvre / Daniel Lebée/Carine Deambrosis

Six months after participating in the Lesser Mysteries, the mystai celebrated the Greater Mysteries and learned the core of Demeter’s secret rites and teachings. According to a fragment by Aristotle, the mystai did not learn anything but underwent an experience that allowed them to share in the emotions of the goddess and provided them with the valuable experience they sought when they came to Eleusis. Upon completion of the ceremony, the initiates could consider themselves happy and possessors of divine revelations that would secure them a better fate in the darkness of the Underworld. There was no requirement for other rituals. However, those interested in gaining a greater understanding and sense of fulfilment could return to Eleusis the following year and participate in the epopteia, the highest degree of initiation.

The decision to participate in the Mysteries could come from various motives. Anxiety about the afterlife certainly affected many believers who sought an assurance of privileged treatment in the Underworld. The story of the Cynic philosopher Demonax is indicative. He was the only one among his compatriots who did not want to be initiated, so it seems that most people who could go to Eleusis, participated in the sacred rites in the Telesterion. Social pressure to participate was also a factor. Gradually, participation in the Mysteries began to have practical benefits in this life. Athenian politicians viewed initiation as a method of increasing their popularity. Alcibiades, who could not miss an opportunity to show off his moral superiority and the abundance of his private wealth, restored the grand procession to Eleusis that had been interrupted during the Peloponnesian War.

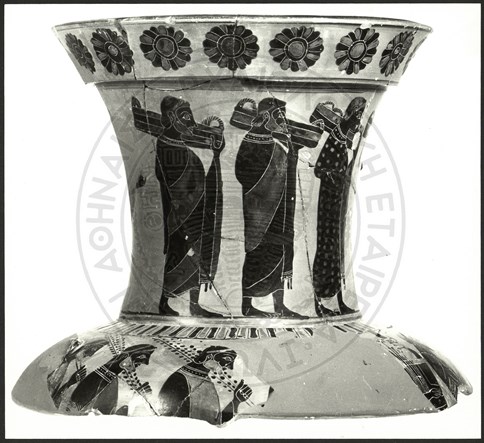

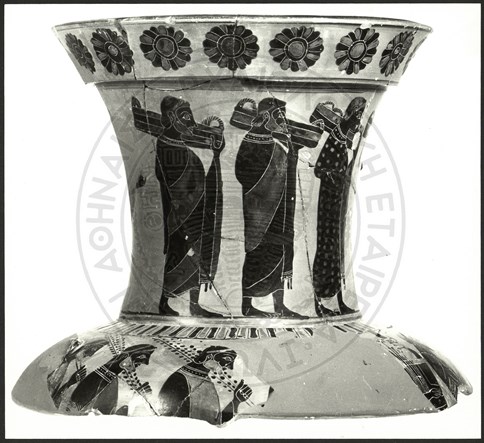

Pyre Γ. Fragment of a black-figure loutrophoros-amphora with a procession of men, Konstantina Kokkou-Vyridi, photograph, Εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία © Η εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία

There does not seem to have been a standard initiation age, and the Eleusinian priests did not (as far as we know) seek to impose age restrictions. Many Athenians, however, seem to have been initiated at a young age. The custom of the hearth initiate was very popular among Athenian families who wished to offer their children as initiates on behalf of the city. The hearth initiate was considered one of the most respected and honoured offices for Athenian boys and girls. Decrees of the second century BCE refer to sacrifices made by Athenian ephebes inside the sacred precinct. Only initiates were allowed to enter this area, so adolescent men must have been initiated before they came of age at eighteen years old. For children, the initiation was an excellent opportunity to receive gifts (in addition to the theoretical benefit of a better life in Hades) from relatives and family friends.