Alcibiades and the Mysteries

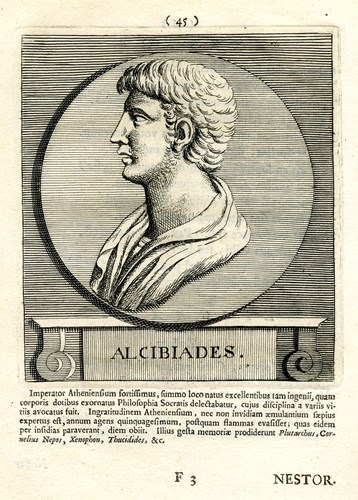

In 415 BCE, Alcibiades, son of Cleinias, was at the height of his power and influence. An extraordinary soul and an embodiment of the pursuit of worldly power, according to Plato, Alcibiades was a prominent Athenian blessed with breathtaking beauty, military prowess, and political acumen. When the Athenians debated the strategy of the Sicilian expedition, they elected Alcibiades as one of the three generals who would lead the massive armada across the sea in an ambitious attempt to capture the island of Sicily.

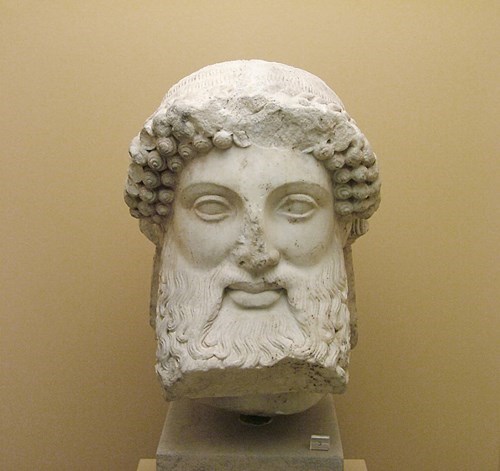

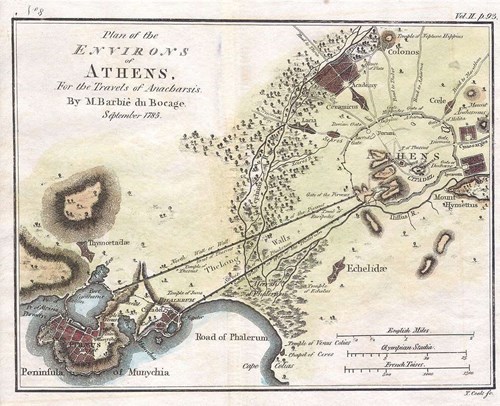

The preparations were quite advanced when disaster struck. On the eve of the fleet’s departure, the Athenians awoke to find nearly every stone marker representing Hermes, placed around the city for good luck, desecrated. The event was considered a bad omen, and informants (“sundry aliens and slaves” according to Plutarch) implicated Alcibiades and his friends. Further investigation revealed a second crime of impiety, even worse than the destruction of the Hermai. The informants claimed that Alcibiades and his friends had made a parody of the Eleusinian Mysteries during a drunken revel. Alcibiades donned the robes of the hierophant and showed forth the sacred objects, while other members of the company played the part of various high priests. Alcibiades hailed those present as mystai and epoptae in clear violation of the ancestral laws of the Eumolpidae and the Kerykes.

His accusers (there was no shortage of political opponents) implied that these sacrilegious acts were connected with a plot against the democratic constitution. The Athenians ordered Alcibiades to return from Sicily and stand trial, but the general defected to Sparta. In his absence, the courts condemned him to death, confiscated his property, and decreed that all priests and priestesses should publicly curse his name. According to custom, they shook their purple robes, turning to the west as they uttered the anathema. Alcibiades’ damnation was also inscribed on a marble stele erected in Athens. In addition, a reward of one talent was decreed for whoever succeeded in killing those who profaned the Mysteries.

The vicissitudes of war and politics kept Alcibiades away from Athens until 411 BCE when the Athenians recalled him and reinstated him as a general. But if the public was willing to forgive his past trespasses, the priests of Demeter were not. On the contrary, they resented Alcibiades throughout his life and did everything in their power to delay his return to Athens. As far as they were concerned, nothing could ever atone for the profanation of the sacred rites of Demeter.

Researched and written by

MENTOR

Bibliography

Lenormant, Francois. “The Eleusinian Mysteries: A study of religious history”, The Contemporary Review, 37 (1880), pp. 847-871.

Levy, Leonard Williams. Blasphemy: Verbal Offense Against the Sacred, from Moses to Salman Rushdie, Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books, 1995.

Edmonds, Radcliffe G., III. “Alcibiades the Profane: Images of the Mysteries in Plato’s Symposium.” In Destrée, Pierre and Giannopoulou, Zina (eds.). Plato’s Symposium: A Critical Guide, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp. 194-215.

Images

1st (and last) image: Map of the City of Athens in Ancient Greece (1784) / Jean-Denis Barbié du Bocage

2nd image: Portrait of Alcibiades (c. 1707) / Pieter Bodart (?) / © British Museum

3rd image: Head of Hermes (5th century BCE) / Ancient Agora Museum in Athens