The earliest mention of Bacchic Mysteries occurs in 500 BCE in a fragment of Heraclitus of Ephesus. Surprisingly, the fragment threatens the followers of Dionysus and the initiates of other unspecified Mysteries (bacchoi, lanai, mystai) with a terrible punishment in the afterlife. This fragment is also the earliest source in Greek literature that mentions the word “mysteria”.

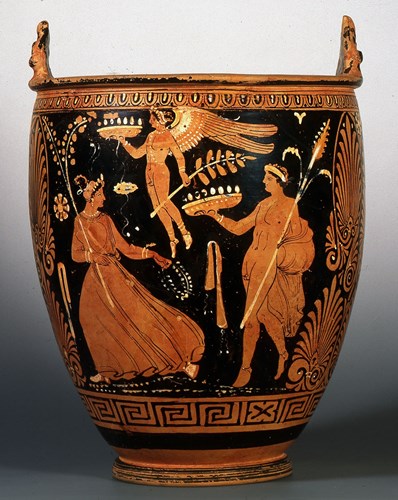

The centre of the cult of Dionysus Bacchus was in the Dodecanese, the neighbouring Greek towns of Asia Minor, and the coast of the Black Sea. The exact process of development that gave rise to the Dionysiac Mysteries remains obscure. The convergence between female maenadic rituals and male Bacchic Mysteries seems to underpin the emergence of the Dionysiac Mysteries, but many questions remain unanswered regarding their chronological development. The original term for a member of a Dionysiac group was “mystes”, but in the Roman period, the word “thiasotes'' became more popular and common. Greek and Roman authors make frequent references to Dionysiac Mysteries but often fail to distinguish between the various elements combined to create them. Common themes are a nocturnal setting, ecstatic dances, sacrifices, and revelations. The phallus and the winnowing fan are the most common iconographic elements.

Situla Form 2 (B: Dionysian Thiasos) (2/5), Painter of Copenhagen 4223, ca. 340-330 BCE, vessel, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg © Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Both men and women seem to have been welcomed into the Dionysiac Mysteries, but there is evidence that some groups were exclusively male or female. The role of women as priestesses was paramount, while men occupied primarily administrative positions. The rites were biennial, even though it is unclear why it should be so. There is also some confusion regarding the part of the year the Mysteries took place. The only indication comes from Callatis on the Black Sea, where the Mysteries were held in the winter month Dionysios. The initiation site was a grove or a grotto (natural or artificial). These could range from crude and undeveloped caves to lovely, custom-built grottos.

As with the Eleusinian Mysteries, secrecy was a quintessential aspect of the Dionysiac Mysteries. Unfortunately, they were also not as popular as the former, so very little information is available regarding the ceremony. An inscription from Torre Nova of about 160–165 CE records hundreds of cult members arranged in several grades, but such a subdivision would have been impractical in small towns. A reference to a holy bath in an inscription from Halicarnassus implies that a bath was an essential component, as with most Mysteries. The sacrifices included cockerels and piglets. The Torre Nova inscription mentions two theophoroi (carriers of the god), who followed a hierophant, a phallophoros (carrier of the phallus), and a pyrphoros (carrier of fire), so there must have been a procession of sorts. Other officials include a narthekophoros (carrier of the narthex), a thyrsophoros (carrier of the thyrsos), a simiophoros (carrier of the statue), a liknophoros (carrier of the winnowing basket), and a kistophoros (carrier of the kiste). The kistophoros was always a woman.

The sacrifice of a goat (an animal closely associated with Dionysus) and night rituals also seem probable. The hieros logos may have included a narrative of Dionysus’ murder by the Titans, implying an Orphic influence. Dances and songs were important, and many funerary epigrams mention dancers and chorus-leaders associated with the Dionysiac Mysteries. Some of the dances may have described the youth of Dionysus and the death of Semele. The philosopher Celsus mentions apparitions (phasmata) and signs (deigmata) that preceded the final revelation: officials (the hierophant, the orgiophant, or the theophant) showed a statue or sacred objects that included a snake, a phallus, sacrificial cakes, and the heart of Dionysus after his murder by the Titans.

Since Dionysus was often depicted in fawnskin, upon completion of the initiation ceremony, the initiates walked away with a belt of fawnskin or a whole fawnskin (the nebris) to display at future meetings. There they could escape from the pressures of urban life in an idyllic countryside setting where they could find some compensation for injustices incurred among their fellow citizens. Being the “chief of the foxes” (archibassara) may not seem like much to our modern sensibilities, but who’s to say what the rank meant to the woman who had the honour to carry it among her fellow Dionysiac initiates?