The Mysteries and European travellers

The destruction of Eleusis by Alaric’s Visigoths in 395 ushered into a long period of decline. The sanctuary lay in ruins that were slowly buried or transported elsewhere for reuse as a building material. In the Middle Ages, the site was occupied by humble huts belonging to farmers and fishers. There is very little information about Eleusis from the sixth to the thirteenth century. In 1204, Michael Choniates, the archbishop of Athens, noted that Eleusis was uninhabited and blamed this scene of desolation on pirate raids that forced the population to seek safety inland.

The earliest visitor who left an account of his passage from Eleusis is Niccolo da Martoni, who misspelt the site’s name as Lippisinox. In 1436, the Italian humanist and antiquarian Cyriacus of Ancona reported piles of ruins and sketched the aqueduct that still stood here and there. In 1675, the English clergyman Sir George Wheler recorded more ruins and the statue of the Caryatid from the Lesser Propylaea that stood among a pile of dung. In 1738, another Englishman, John Montague, reported the destruction of numerous sculptures by the Turks. In 1755, the French architect and archaeologist Julien-David Le Roy observed the remains of “fine marble temples, great aqueducts, and other traces of [Eleusis’] former splendour”. He mistook the Caryatid for a statue of Demeter and lamented the ruinous state of the Telesterion.

Ten years later, the Society of Dilettanti dispatched Richard Chandler, the architect Nicholas Revett, and the painter William Pars to study the ruins of Eleusis. This was the first serious attempt to scientifically study the sanctuary’s remains and resulted in a series of fine drawings. Chandler thought he recognised a statue of Persephone in the Caryatid and located a sculpture of crossing torches among the ruins. He also mentions an inscription on the base of a statue that would have depicted a priestess of Demeter that had covered the altar of the goddess in silver.

The Dilettanti expedition initiated a period of reinvigorated interest in Eleusis, even though most travellers could only study (however perfunctorily) the “miserable village” that occupied the site of the ancient sanctuary. The remains of ancient Eleusis were deemed insignificant; only a few stones stood upright, and the ravages of time and unscrupulous foreign visitors resulted in a rapid deterioration of whatever traces of the past still existed. Finally, in 1812, the Society of Dilettanti returned to begin the excavation of the site under the directorship of Sir William Gell. He investigated the Temple of Artemis Propylaea and the Greater Propylaea. He also managed to determine the location of the Telesterion, which had been overbuilt with houses.

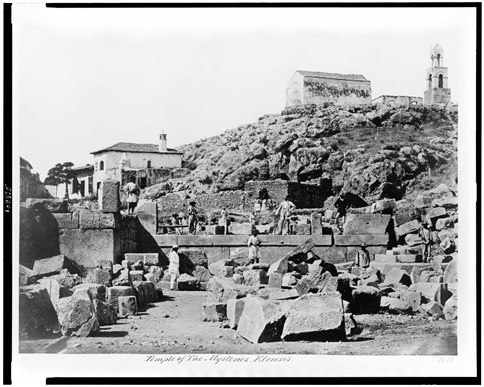

Temple of the Mysteries, Constantine Dimitrios, ca. 1850-1880, photograph, Library of Congress © Library of Congress