Alexander of Abonoteichus was a Greek mystic, oracle, and founder of the popular Glycon cult that took the Roman world by storm in the 2nd century. But unfortunately, he was also a complete phoney, a crook of unparalleled proportions, an impostor who invested his considerable talents in defrauding people and engaging in all forms of thuggery. In the autumn of 169, Alexander unexpectedly found himself holding the future of the Roman Empire in his hands. And he really dropped the ball.

For the past three years, the Roman authorities on the Danube watched with alarm as various barbaric tribes came ever closer to the border. The cause of their migration was pressure by the Goths, who were moving south from the steppes of Russia and expelled people from their homes. These migrants had to look for new land further south. The rich and fertile lands of the Roman Empire was a natural magnet, but the Roman legions served as an impregnable barrier to their movement. In theory. In practice, though, the Roman army was weak and ineffectual. Marcus Aurelius, fully aware of the impending danger, was forced to move his troops along the border to strengthen the weakest points, especially in the lands north of Italy. Alexander, the self-appointed prophet of a deity he had conjured out of thin air, instructed the emperor to sacrifice to Glycon. He commanded Marcus Aurelius to hurl into the Danube “a pair of Cybele's faithful attendants [i.e. lions], beasts that dwell on the mountains, and all that the Indian climate yieldeth of flower and herb that is fragrant”. The lions were duly thrown into the river and swam to the opposite shore where the Marcomanni slaughtered them with clubs, thinking them some kind of foreign dogs or wolves. And then, the barbarians crossed the border and killed twenty thousand Roman soldiers.

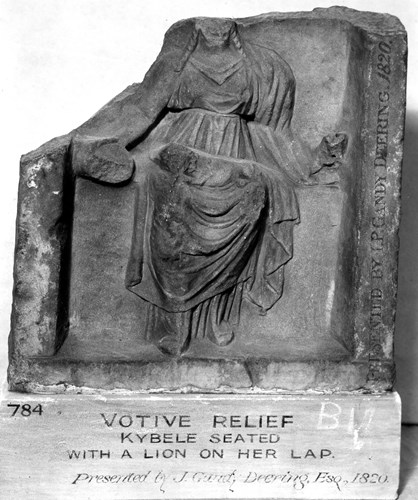

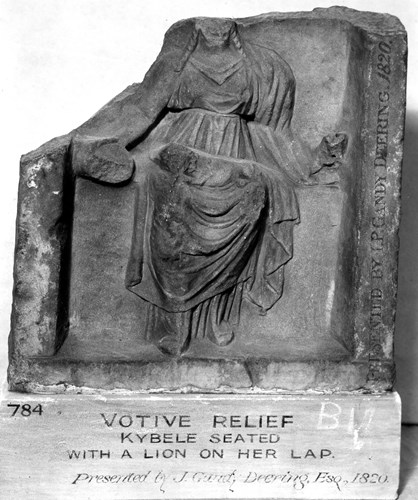

Marble votive relief in form of Cybele seated within naos with lion in lap, 420-350 BCE, sculpture, The British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum

While the Roman army tried to control the invasion of the Marcomanni though, another tribe decided to explore the opportunities offered by the prosperous Roman lands in the Balkans. The Costoboci were a tribe of Thracians who lived east of the Carpathian Mountains in present-day Romania. Their settlements were north of the Roman province of Dacia, and they were therefore considered free Dacians. In 170 CE, the Costoboci decided to invade the Roman lands to the south. Perhaps it was a simple, old-fashioned raid for loot or an attempt at a permanent settlement to escape from the Goths who were advancing towards their own lands. The Roman forces had been weakened to shore Roman defences further west, so the Costoboci were able to race through Dacia, Macedonia, and southern Greece. Any town that lacked defensive walls fell victim to their predations. This army of bandits (according to Pausanias) was able to rout any local militias that tried to block their advance and left behind them a trail of tombs full of soldiers who perished in an attempt to defend their homeland.

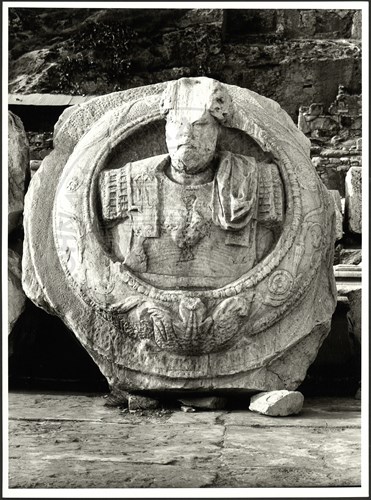

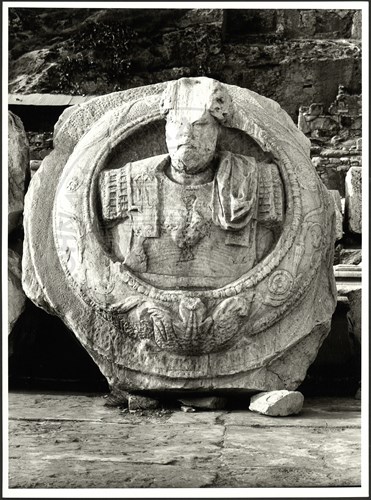

In late summer 170 CE, the Costoboci arrived in Eleusis and burned some sanctuary buildings. The following summer, the Greek orator Aelius Aristides lamented the calamity that struck Demeter’s sanctuary before an audience in Smyrna (modern Izmir) that could hardly believe their ears. The notion that barbarians could reach the heart of the Roman Empire must have been a tremendous shock to a population long accustomed to the calm days of Pax Romana. But it was not long before the Roman state was able to regroup and attack. Imperial forces landed in Greece and drove the Costoboci back across the Danube. As for Eleusis, the emperor proved more than willing to atone for his disastrous abandonment of the goddesses. Marcus Aurelius rebuilt the Telesterion and Philon’s porch. He added a medallion with his portrait on the pediment of the Greater Propylaea to remind everyone that he had managed to defeat the barbarians and secure the safety of the sanctuary and the empire.

The Greater Propylaea. The bust of Marcus Aurelius on the pediment, Demosthenes Ziro, 1984, photograph, Εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία © Η εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία