Alaric and the last hierophant

In the early 360s, the Armenian Christian teacher and rhetorician Prohaeresius asked the hierophant in Eleusis to predict the duration of the measures adopted by Emperor Julian against the Christians. There is no certainty as to the hierophant’s identity. Still, it seems probable he was Nestorius, one of Julian’s principal councillors who the emperor had commissioned to restore the cult of Demeter in Eleusis. Eunapius, historian and biographer of the last Greek philosophers and orators studied under Prohaeresius and referred to the sanctuary’s decline in the late fourth century.

A hierophant from the genus of the Eumolpidae had initiated Eunapius, but he was also unable to hide his fears about the future. The hierophant (Eunapius refuses to reveal his name) prophesied the overthrow of the venerable temples and the death of the religious tradition that would occur with the consecration of a man not of Athenian origin to the office of Demeter’s highest priest. This man would have no right to approach the hierophant’s throne because he was dedicated to other gods and had sworn terrible oaths never to preside over other ceremonies. The last hierophant, illegitimate though he would be, would live long enough to see the end of the worship of the two goddesses, the destruction of the sanctuary, and the people's scorn.

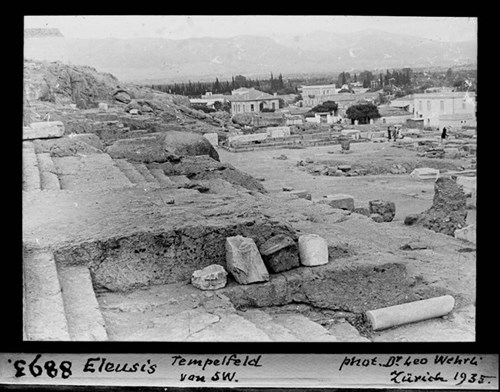

It did not take long for these terrible predictions to come to fruition. Upon the death of the last legitimate hierophant, a man from Thespiae, who was also a priest of Mithras, became hierophant. The ancient religious tradition was dying, and the remaining pagans could not preserve it. Much like the last hierophant had anticipated, a terrible disaster befell Eleusis. Scarcely had the priest of Mithras become hierophant when the hordes of the Visigoths under Alaric burst through the pass of Thermopylae and unleashed a wave of destruction over the Greek cities and sanctuaries.

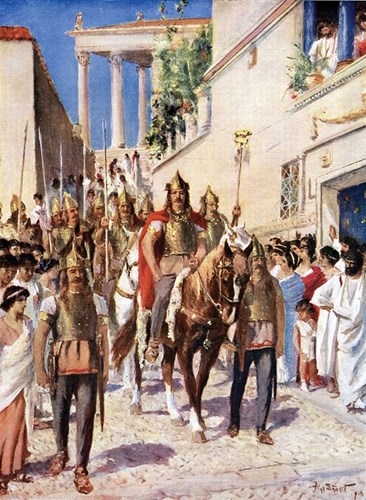

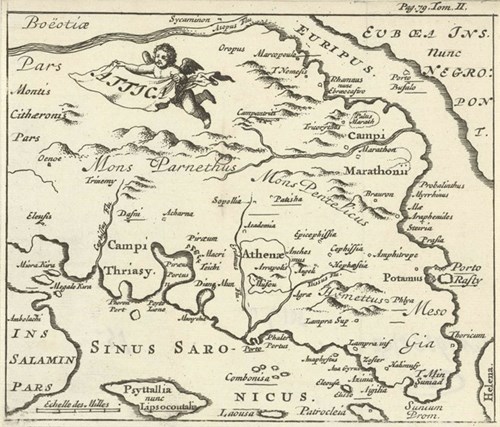

Alaric was in the service of the Roman empire, but he felt scorned and neglected. When he did not receive the advancement he expected, he quit the imperial service, amassed an army and embarked on a campaign against the Roman Empire. In 395, he advanced to the walls of Constantinople but soon turned south, ravaging Thessaly. When the northern provinces were exhausted, Alaric invaded southern Greece. The civil and military commanders of Achaia left Thermopylae unguarded and allowed Alaric to enter Greece without any resistance. Eunapius described the swift advance of the Goths in 396 as though they were running down a racecourse, a field stamped by horses. They burned towns and villages, murdered men, and carried women and children as slaves. The town of Eleusis suffered greatly. The Goths plundered the residences and the sanctuary before setting everything on fire. Whether the fire resulted from wanton love of destruction or a systematic attempt by the monks who accompanied Alaric to extirpate one of antiquity’s greatest pagan sanctuaries remains unclear.

The effect of Alaric’s invasion was devastating. Eleusis never recovered from the attack. The year after the burning of the sanctuary, Claudius Claudianus, court poet to the western emperor Flavius Honorius, wrote an unfinished poem called De Raptu Proserpinae in which he lamented the destruction by “the black horses of that thief from the underworld, the stars blotted out by the chariot’s shadow”. For Claudianus, Alaric’s raid was similar to the rape of Persephone and the fall of Eleusis a real-world re-enactment of Kore’s loss by Hades.

Bibliography

Finlay, George. Greece Under the Romans: A Historical View of the Condition of the Greek Nation, from Its Conquest by the Romans Until the Extinction of the Roman Empire in the East, B.C. 146- A.D. 716, London: W. Blackwood, 1857.

Kerényi, Carl. Eleusis: Archetypal Image of Mother and Daughter, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Lavan, Luke και Mulryan, Michael (eds.). The Archaeology of Late Antique 'Paganism', Leiden: Brill, 2011.

Image sources

École nationale supérieure des Beaux-arts de Paris - Victor Blavette (1884): The sanctuary of Demeter.

ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv - Leo Wehrli (1935): Excavations in the sanctuary of Demeter in Eleusis.

Wikipedia Commons - Unknown artist (1920s): Alaric enters Athens.

Rijksmuseum - Jan Luyken (1679): Map of Attica.

Victoria Art Gallery - Joshua Cristall (c. 1768–1847): The Rape of Persephone.