Aeschylus and the Eleusinian Mysteries

Aeschylus was born in 525 BCE in Eleusis. According to tradition, his father, Euphorion, was a priest of the Eleusinian Mysteries and other family members served as hereditary priests. Aeschylus fought bravely in defence of his homeland against the Persians at Marathon, Salamis, and Plataea before embarking on a glorious career as a tragedian.

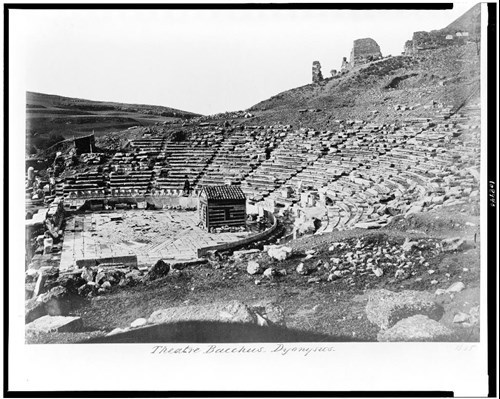

At an unknown time, Aeschylus was accused of impiety for revealing certain features of the Eleusinian Mysteries on stage during the performance of a play. The details of the affair are obscure. The Greek philosopher Heraclides Ponticus asserts that the audience tried to kill the dramatist on the spot, but Aeschylus took refuge at the altar in the orchestra of the Theatre of Dionysus. During the subsequent trial, he claimed he was not an initiate and therefore could not reveal secrets he did not know were secrets. The Greek military writer Aelianus Tacticus, who lived many centuries after these events, preserved a story that the jurors acquitted Aeschylus after a passionate plea from his younger brother, Ameinias, who appeared in court and showed those presents the stump of the hand he had lost at Salamis.

There are certain interesting features in this apocryphal story. Suppose we accept Aeschylus’ claim about his ignorance of the Mysteries. In that case, we can assume that they were not as universally popular in the early fifth century as they would become a few decades later. As an Eleusinian, it would have been natural for Aeschylus to have been initiated if the practice was widespread. Only a few years after Aeschylus reached adulthood, the exiled Spartan king Demaratus, who was following the Persian army in the retinue of King Xerxes, was not familiar with the rites of Demeter and could not comprehend the meaning of the voice emanating from the cloud approaching the Persians from the direction of Eleusis on the eve of the battle of Salamis (480 BCE).

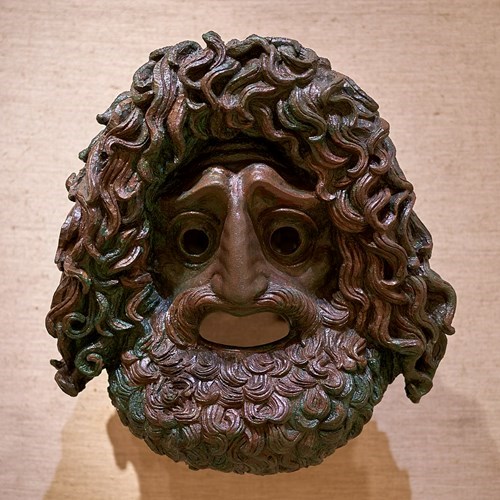

On the other hand, it seems unlikely that the story is devoid of truth, even if we never discover the actual facts. An extended biographical tradition recognises a connection between the Eleusinian Mysteries and the performances staged by Aeschylus. The playwright is credited with designing costumes of such comeliness and dignity that the hierophants and the daduchs adopted them. The Eleusinian Anaktoron may also have served as a model for the skene by Aeschylus. If that is the case, perhaps the Athenians were uncomfortable with the dramatic practice of actors coming on stage to reveal corpses and acts of murder in a way reminiscent of the hierophant exiting the Anaktoron to display the sacred objects of Demeter’s rites.

Researched and written by

MENTOR

Bibliography

Sourvinou-Inwood, Christiane. Tragedy and Athenian Religion, Oxford: Lexington Books, 2003.

Gould, Thomas. The Ancient Quarrel Between Poetry and Philosophy, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Kippenberg, Hans και Stroumsa, Guy (eds.). Secrecy and Concealment: Studies in the History of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Religions, Leiden: Brill, 2018.

Images

1st (and 4th) image: George E. Koronaios: Greek tragedy mask (4th cent. BCE) / Archaeological Museum of Piraeus

2nd image: Gebbie & Husson Company, Ltd. (1889): The Vanquishers of Salamis / The Metropolitan Museum

3rd image: Unknown (1850): Theatre of Dionysus, Athens / Library of Congress

5th image: Pronomos Painter (400 BCE): Ancient Greek actors (detail / Museo Nazionale Archeologico