The Greater Propylaea

The Greater Propylaea

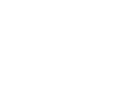

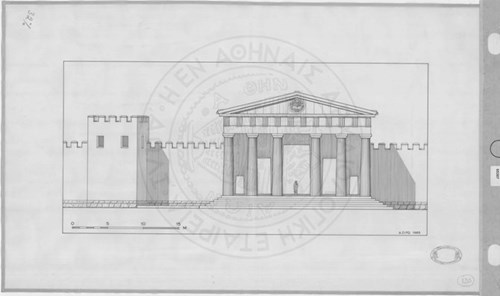

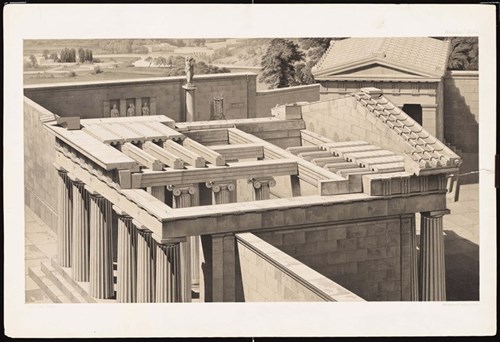

The Greater Propylaea is a copy of the monumental propylaea designed by Mnesikles for the Acropolis of Athens. The only essential differences (apart from the quality in the construction, which is inferior in the case of the propylaea of Eleusis) are the absence of the side wings and the omission of the central corridor of the Athenian Propylaea.

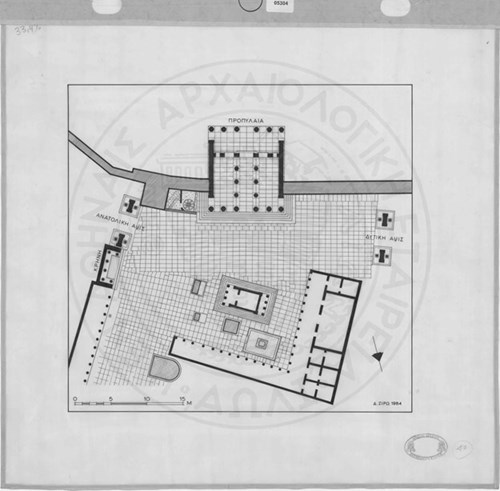

The Greater Propylaea stand on a pedestal, which rises 1.70 metres (5.6 feet) from the level of the paved courtyard. It is not located on the central axis of the yard and faces Athens in the northeast. Like other Roman buildings of the period, the core of the stairways is made of concrete hidden behind an isodomic masonry (composed of stones of uniform size). The rest of the building is made of Pentelic marble and consists, essentially, of a transverse wall with five entrances and two porches (exterior and interior). The outer portico had six Doric columns (in groups of three), a simple entablature, a frieze with alternating triglyphs and metopes and a triangular pediment.

A Roman emperor bust was carved on a shield in the tympanum (imago clipeata). Unfortunately, the facial features have been irreparably damaged, making it difficult to identify the person depicted. The giant, displayed on the shoulder strap, suggests that it is Marcus Aurelius and recalls the emperor's triumph against the Germanic tribe of the Marcomanni in 172/3 AD. The Gorgon on his chest is a subtle reminder that Marcus Aurelius is not inferior to Zeus, who crushed the Giants. The Christians carved the large cross on the Gorgon to exorcise pagan spirits.

The Propylaea were accessible by a flight of stairs. The lower stops abruptly on the east side to leave room for the Kallichoron well. An entrance was constructed that gave access to the well using a wooden ladder.

The Greater Propylaea suffered severe damage and loss of material over the centuries. Only the bases of the columns are left in situ, while two columns have been assembled in the courtyard nearby. Even the transverse wall has almost wholly disappeared. Only the lower layer remains and allows us to distinguish the five openings, gradually growing smaller from the centre to the sides. The threshold of the smaller door on the left is visibly more worn than the rest, indicating that most visitors entered the sanctuary through this entrance, which may have been the only one left open daily.

In later Roman times, the outer colonnade was closed by a wall that left only one entrance in its centre. The wall was undoubtedly a response to some extraordinary and grave danger facing Eleusis. It is connected, perhaps, with the effort made by the authorities to strengthen the defence of the sanctuary during the period of the catastrophic invasion of the Goths and the Heruli so that we could attribute the wall to the emperor Valerian (253-260).

The inner side of the Greater Propylaea also had six columns. Unfortunately, only the first drum of the western column remains in place.

After the sanctuary’s destruction, Christians carved crosses in many parts of the Propylaea, in an attempt to keep away the pagan spirits that supposedly haunted the building.

Bibliography

Αλεξοπούλου-Μπαγιά, Πόλλυ. Ιστορία της Ελευσίνας: Από την Προϊστορική μέχρι τη Ρωμαϊκή περίοδο, Ελευσίνα: Δήμος Ελευσίνας, 2005.

Cosmopoulos, Michael. Bronze Age Eleusis and the Origins of the Eleusinian Mysteries, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Kourouniotis, Konstantinos. Eleusis: a guide to the excavations and the museum, Athens: The Archaeological Society at Athens, 1936.

Mylonas, George. Eleusis and the Eleusinian Mysteries, London: Routledge, 1962.

Papangeli, Kalliopi. Eleusis: the archaeological site and the museum, Athens: Omilos Latsi, 2002.

Image sources:

Architekturmuseum TU Berlin - Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1830s): The Greater Propylaea.

The Archaeological Society at Athens - Dimosthenis Ziro (1984): The main entrance to the sanctuary at the time of Hadrian; Dimosthenis Ziro (1984): The Greater Propylaea (late 2nd century CE); Dimosthenis Ziro (1984): The Greater Propylaea at the time of Pausanias (160 CE).

The J. Paul Getty Museum - Petros Moraites (1860s): The Greater Propylaea