The first fruits

Famine was a constant threat hanging over the leads of ancient agricultural communities. Lousy weather, war and plunder, or a severe pandemic could destroy the crops and condemn the citizens of a town or region to hunger and deprivation. The story of Demeter and Persephone expresses this danger in the most poetic fashion possible. When Demeter, struggling to cope with the loss of her daughter, refused to leave her temple, the earth stopped producing food, and humanity came face to face with extinction. However, the timely intervention of Zeus and the return of Persephone from the dark realm of Hades averted disaster. But it did not eradicate the threat of famine.

At some point in time (ancient sources disagree on the Olympiad during which the following events unfolded), a deadly combination of famine and disease brought the human race close to annihilation. Even the mythical land of the Hyperboreans witnessed a complete failure of crops, a precursor to an unheard-of apocalypse. Terror reigned in every mortal soul, and all eyes turned to the gods in search of salvation. According to an oracle by Apollo, the Athenians had to offer a sacrifice on behalf of humanity. Abaris the Hyperborean came to Athens holding an arrow and announced the divine judgment to the people. The ambitious citizens of Athens gladly assented to offer the necessary sacrifices on behalf of the Greeks. Ever since, the Greek cities agreed to send a tithe (aparche) of the annual grain harvest to Eleusis in memory of their salvation.

This promise did not seem to bind the cities forever. On the contrary, there were long periods when only Athenian demes and cleruchies (a type of colony established by Athens) contributed systematically. The other Greek city-states only honoured the custom when the Mysteries were popular, and the power of Athens could forcefully remind them of the ancient tradition of the first fruits.

As the Mysteries approached in the middle of the month of Boedromion, the Hierophant dispatched messengers (spondophoroi) to announce the beginning of the sacred truce and invite Greek cities to send the first fruits to Eleusis. It was a delicate diplomatic mission of the utmost importance for the sanctuary. Each spondophoros had to carry a custom message according to the audience that would receive it. The Hierophant who prepared the message and the messenger who delivered it had to be familiar with each place’s unique relationship to Eleusis and local traditions to avoid a diplomatic blunder.

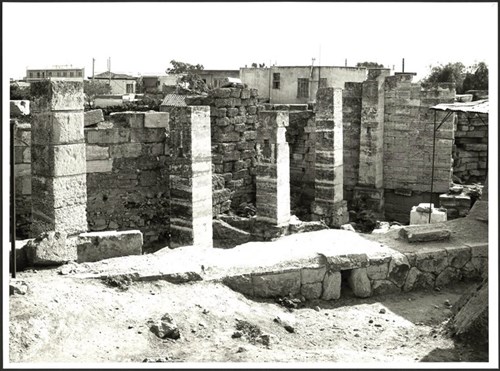

Farmers did not have to wait to complete the harvest before dispatching the first fruits to Eleusis. The barley harvest in southern Greece begins in early May, while the wheat harvest follows a few weeks later. But there was no reason to wait for the completion of the process. The first fruits were precisely that: the first grain harvested by farmers each year. The localities delivered the aparche to Eleusis, and the authorities stored it in large granaries called siroi. The grain did not remain there long. The purpose of the aparche was to provide for sacrifices to the gods and the mythical ancestors of the Eleusinians.

Within a few weeks, the doors of the granaries opened, and the aparche was put into good use. The first sacrifice was called pelanos. Then the aparche was sold, and the proceeds from the sale funded sacrifices to Demeter, Kore, Triptolemos, Theos, Thea, Euboulos, and Athena. Demeter and Persephone received one bull, one sheep, and one goat each. The other deities were entitled to a sheep or goat, except for Athena, who received a bull. Occasionally, the Eleusinians would offer more animals. In 328 BCE, they sacrificed forty-three sheep and goats, but we do not know how they distributed the animals per deity.

The quantity of grain that arrived in Eleusis was quite large. For example, in 328 BCE, the localities delivered 1108 medimnoi (57439 litres) of barley and 87 medimnoi (4510 litres) of wheat. From the total amount of grain, one medimnos was used from the prokonia (cakes made of barley or wheat) given to the hieropooi, and sixteen medimnoi were used for the pelanos (a pottage made of wheat and barley). The authorities maintained detailed accounts of the quantities delivered to the sanctuary. Thus, they could spot cheating whenever there was a significant discrepancy in the amount of grain that arrived in Eleusis.

After the sacrifice expenses, any money left was used to set up dedications in the sanctuary on behalf of all the Greeks. It was a great propaganda opportunity for the Athenians to remind the other Greeks of the gratitude they owed to Athens for their salvation at the time of the great famine. In wartime, the money was safely stored in the Acropolis as income of the Eleusinian sanctuary for use at a more propitious time.

Bibliography

Clinton, Kevin. The Sacred Officials of the Eleusinian Mysteries, Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 1974.

Clinton, Kevin. “The Eleusinian Aparche in practice: 329/8 B.C.” in Λεβέντη, Ιφιγένεια και Μητσοπούλου, Χρυσούλα. Ιερά Και Λατρείες Της Δήμητρας Στον Αρχαίο Ελληνικό Κόσμο, Βόλος: Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλίας, 2010, pp.1-12.

Mylonas, George. Eleusis and the Eleusinian Mysteries, London: Routledge, 1962.

Parker, Robert. Polytheism and Society at Athens, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Suk Fong, (Theodora) Jim. Sharing with the Gods: Aparchai and Dekatai in Ancient Greece, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Image Sources:

Roman sculptures at the Archaeological site of Eleusis. Haris Andronos, Shutterstock

Siroi (magazines) of Roman times at the Archaeological site of Eleusis. Ephorate of Antiquities of West Attica

Roman sculptures at the Archaeological site of Eleusis. siete_vidas, Shutterstock