The early relationship between Eleusis and Athens is controversial. Researchers contest the date at which the Eleusinian Mysteries were incorporated into Athenian religion and whether the rites derive from a Mycenaean cult that eventually became part of Athenian state religion. Tradition claims that the two cities went to war at some point, with Athens annexing Eleusis after a protracted struggle. The war claimed the lives of Erechtheus, king of Athens, and Eumolpus, king of Eleusis (or his son, Immarados). The Eleusinians received assistance from Skiros, a son or grandson of Poseidon, the god of the sea, but the Athenians prevailed when the youngest daughter of Erechtheus sacrificed herself. Another mythological tradition, mentioned by Pausanias and Strabo, dates the war to the time of Ion, whose superior strategy ensured the triumph of the Athenian army. Even though different in their details, all these traditions conclude in the same way: the annexation of Eleusis by Athens.

Whatever the exact historical procedure, the relationship between the two enemies had been cemented by the late archaic period. The Mysteries were regulated by the Archon Basileus in Athens (a magistrate charged with overseeing the organisation of religious ceremonies and presiding over homicide trials) and the Eleusinian priesthood. The political unification of Attica went hand in hand with the absorption of local cults by Athens. The cult of Artemis at Brauron had a branch on the Acropolis. The statue of Dionysus Eleuthereus was brought to Athens when Eleutherae was annexed. The same process marked the annexation of Eleusis. Athens henceforth celebrated the Mysteries with a grand procession from Kerameikos to the sanctuary of Demeter in Eleusis.

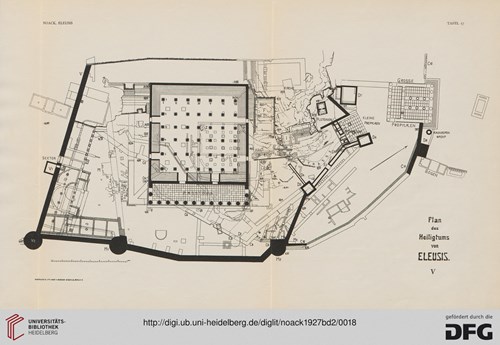

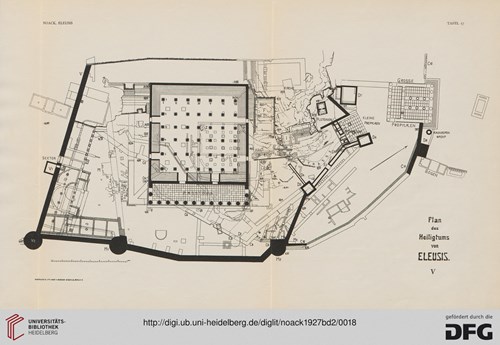

Plan of the sanctuary of Eleusis V, Ferdinand Noack, 1927, engraving, Universität Heidelberg © Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg / Public Domain

The Athenians dedicated considerable effort into reinforcing their Eleusinian credentials. The city claimed to be the site of Persephone’s rape (the Homeric Hymn to Demeter was conveniently vague on the location of the incident). The Athenian atthidographer Phanodemus placed the rape firmly in Attica, while the Orphic Hymns (long considered to incorporate Eleusinian mythological traditions) linked the rape to the topography of the Thriasian Plain. The Athenians also claimed to have been the first to receive the gift of grain from Demeter. They were generous and spread it to the rest of the world. The invention of agriculture reinforced their other claim of inventing civilization. Isocrates did not mince his words when he proclaimed for all Greeks to hear that the Athenians “were not only so beloved by the gods but also so benevolent to mankind that, having gained power over such great good things [agriculture and the Mysteries] ... shared with everyone what they had received.” Triptolemus, who had spread knowledge of agriculture throughout the world, became the quintessential Athenian hero, a popular figure on Attic vases and sculpture and a poster boy for Athenian benevolence, magnificence, and imperial prowess.

Ceres, Proserpine, Triptolemus, 50 BCE - 50 CE, sculpture, Musée du Louvre © 2013 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Tony Querrec

Attic drama was also heavily influenced by Eleusinian myth and shaped the relevant stories to serve the audience’s political and imperial sensitivities. For example, in his lost play Eleusinians, Aeschylus drew inspiration from a local tradition that King Theseus allowed Adrastus to bury the leaders of the ill-fated Argive expedition against Thebes in a cemetery near Eleusis. When the Thebans refused Adrastus the right to recover the bodies of the fallen heroes, Theseus and the Athenians went to war to bring their remains to the Athenian territory. The animosity between Athens and Thebes was longstanding, so Aeschylus had no qualms about using a local Eleusinian story to cast Athens into the righteous light of adherence to the ancestral laws governing the disposal of the dead while taking a political jab against the Thebans.

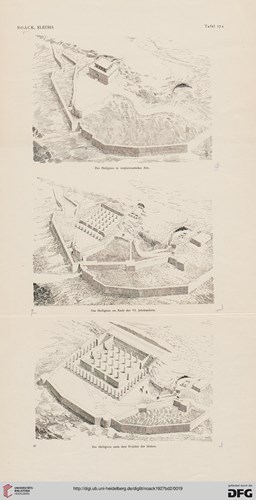

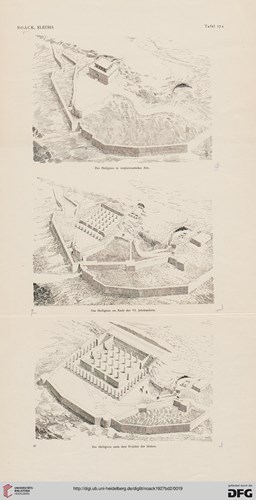

The Athenians also invested heavily in the prestige and magnificence of the Eleusinian Mysteries, thinking that the grandeur of Demeter reflected the brilliance of their city and constitution. Grand building programmes endowed the sanctuary with impressive buildings that advertised Athenian piety and political ambitions. As the Mysteries became more popular throughout the Greek world, the leaders of Athens worked to make them more impressive and open. Peisistratos expanded the Telesterion and protected the sanctuary with imposing walls to transform Eleusis into a bastion against Megara. Pericles funded a significant building program that increased the temple's capacity and endowed the sanctuary with elegant monuments.

The evolution of the Telesterion, Ferdinand Noack, 1927, engraving, Universität Heidelberg © Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg / Public Domain

Finally, the political importance of the Mysteries and the sanctuary is best reflected in the use of the first fruits. In the 430s, the Athenians issued a decree asking (not too politely) their allies to send first-fruits to Eleusis. It was accompanied by a reminder that it was the Athenians who saved humanity from famine back in the day when all crops had failed, and Delphi ordered them to sacrifice on behalf of all Greeks. The sale of the first fruits funded sacrifices and the setting up of dedications in Eleusis. Still, in exceptional circumstances, such as wartime, the money stayed on the Acropolis as income of the Eleusinian sanctuary and as a valuable reserve for the Athenians should they need access to large amounts of money for their war efforts.